Climate change has brought about a myriad of environmental, social, and economic challenges, reshaping ecosystems and human livelihoods across the globe. Rising temperatures, erratic weather patterns, and prolonged droughts have intensified water scarcity, making access to clean water increasingly precarious for millions. As rivers dry up, groundwater depletes, and rainfall becomes unpredictable, communities that once thrived on stable water sources are now facing displacement. This growing crisis is not just an environmental issue but a humanitarian one, forcing families to abandon their homes in search of water security and survival.

The Growing Crisis: Water Scarcity and Climate Change

The issue of water scarcity represents a significant worldwide challenge, impacting billions of people and exacerbated by climate change. In 2022, 703 million people did not have access to water, and more than 2 billion lack safe drinking water. It is estimated that by the end of 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in areas that face absolute water scarcity.

Climate Migration

Water is essential for life, and its scarcity, fueled by climate change, has become a significant driver of human migration worldwide. As freshwater resources dwindle due to prolonged droughts, erratic rainfall, and overuse, communities, particularly those reliant on agriculture and livestock, face mounting challenges to their livelihoods and survival. This environmental stress compels many to relocate in search of more hospitable conditions.

Real Stories of Displacement due to Climate Induced Water Scarcity

Climate induced water scarcity has compelled numerous communities worldwide to abandon their homes in search of more sustainable living conditions. These personal narratives highlight the profound human impact of environmental crises:

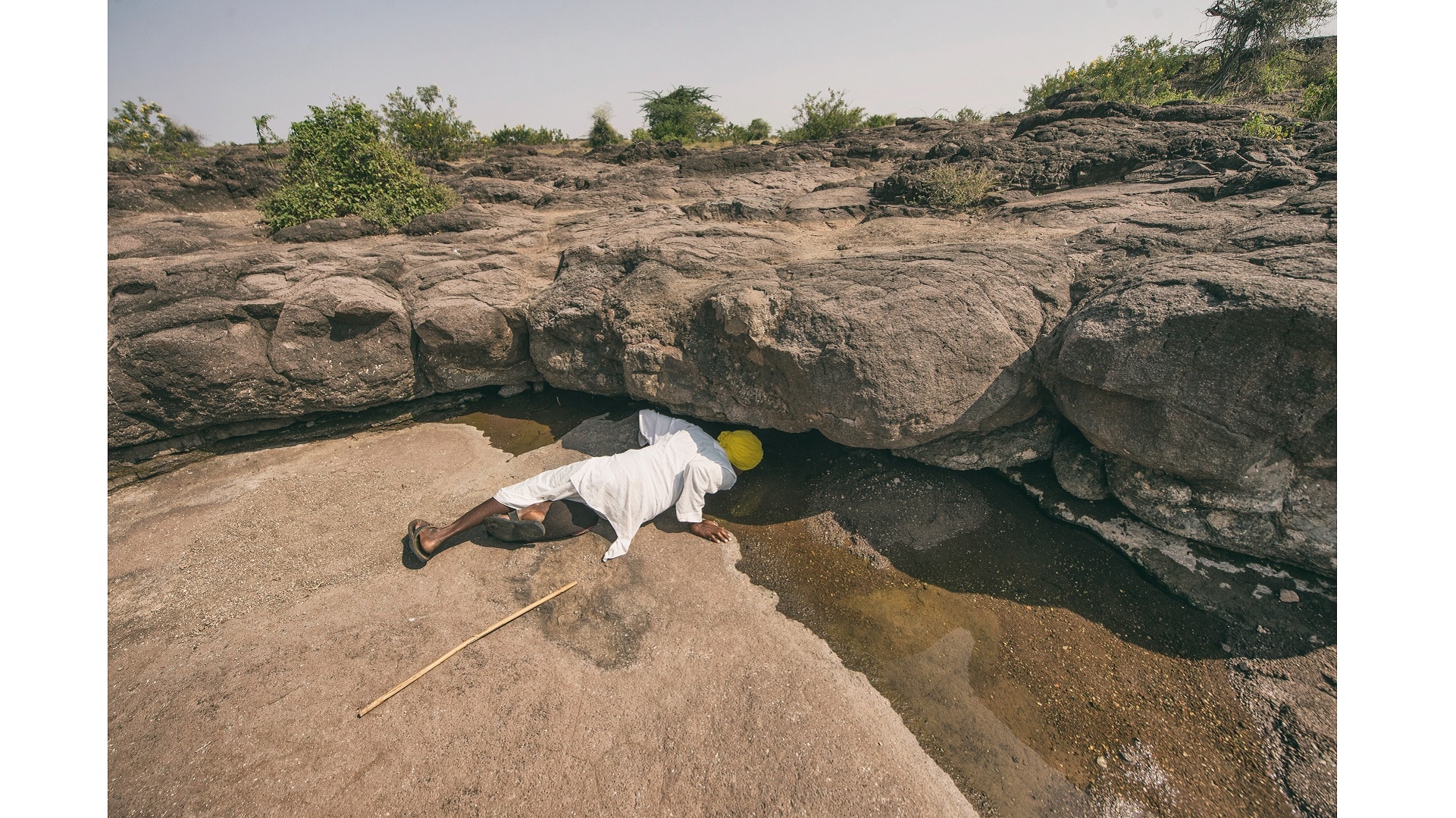

Hatkarwadi, Maharashtra, India: A Village Deserted

Hatkarwadi, a village in Maharashtra’s Beed district, exemplifies the severe impact of water scarcity. Once home to over 1,200 residents, the village has been largely abandoned due to prolonged drought conditions. With 33 of its 35 wells dried up, and the remaining two containing minimal water, agricultural activities became unsustainable, forcing families to migrate in search of better living conditions. The exodus left only a handful of individuals behind, underscoring the profound effect of water shortages on rural communities.

Hatkarwadi, a village without rain (Image Courtesy: BBC)

Somalia: Fleeing Drought and Hunger

In Somalia, a prolonged drought has displaced over a million people since January 2021. Families, such as those in the Daryel Shabellow camp, have seen their livelihoods decimated by four consecutive years without rain. Farmers Mohamed Hassen, 71, and Madina Omar, 70, were compelled to leave their barren farmland after losing all their crops. Madina reflects, “We lost everything at home, but we also don’t have anything here.”

Parched land, empty hands—Bora Robu Etu’s family walks through the night for water, as drought steals their future (Image Courtesy: Unicef Ethiopia)

Ethiopia: Seeking Water and Shelter

In Ethiopia’s Somali Region, around 500 internally displaced families reside in makeshift shelters at the Mara-gaajo site in Kebribeyah. They fled their homes during one of the worst droughts in decades. Ardo, a displaced individual, describes the severity: “We have never seen drought like this; it has affected everyone. We have named it ‘the unseen’.”

What Exactly Can We Do?

Hearing these stories can often make you feel hopeless. But there can be solutions. At the grassroots level, we can tackle water scarcity by adopting sustainable water management practices such as rainwater harvesting, efficient irrigation, and wastewater recycling. Governments and communities must support climate-adaptive agriculture, encourage water-saving practices, and invest in resilient infrastructure. To develop proactive solutions for a safer and sustainable future, cooperation between legislators, scientists, and local stakeholders is crucial. Ultimately, addressing this crisis requires urgent and sustained action to protect both people and the planet.

/india-rajasthan-jaipur-water-tank-for-rain-168640178-5914780b3df78c9283cb0222-5a663cb2e33dec00370c737e.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/dd/12dda8c5-49b7-41e5-89fd-6b01d958e693/42-65785369.jpg)